Staying Power

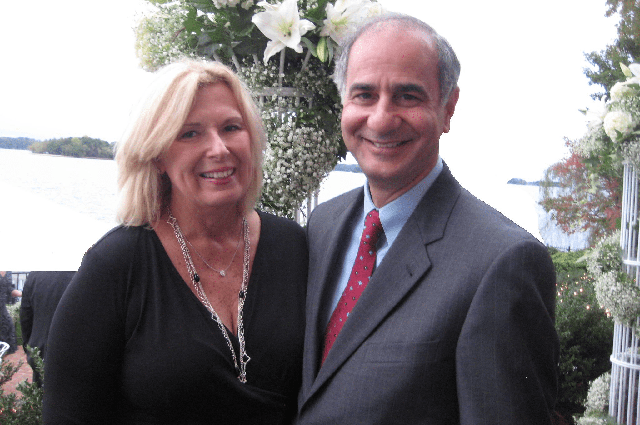

Carolyn Birmingham shares her passion for engineering by supporting the Center for STEM Diversity

Carolyn O’Connor Birmingham, E57, remembers when women counted career options on one hand. “Professionally,” said Birmingham, “they were teachers, or they were nurses, or perhaps social workers.” Birmingham had other ideas.

She earned a degree from the Tufts School of Engineering—one of only three women to graduate from the school in 1957—and went on to a career at Cambridge-based General Radio.

Today, she is happy to do what she can for young people who have big dreams and limited means. Her gifts are benefitting Tufts students from low-income families who aspire to careers in STEM—science, technology, engineering, and math. She and her late husband, James, first endowed a scholarship in 2006. More recently, she also started supporting the Center for STEM Diversity.

“I was excited that Tufts has a program that gives extra support to students who need it and that creates a place where they feel they belong,” she said. “I know from my work in town governance that diverse opinions and experiences are likely to lead to good decisions. The center understands that diversity in STEM is critical to success in the workforce.”

Ellise LaMotte, director of the Center for STEM Diversity, appreciates Birmingham’s philanthropy as well as her engagement as a member of the center’s advisory board. Birmingham has supported the STEM Ambassadors Program, which sends Tufts undergraduates into high schools to share their passion for science and engineering. She also made it possible for Bridge to Engineering Success at Tufts (BEST) students to attend the Tufts in Talloires summer program.

“Carolyn has been instrumental in making the Center for STEM Diversity successful and allowing students to have experiences they might otherwise not be able to have,” said LaMotte. “We’re fortunate to have a friend like Carolyn supporting us, not only monetarily, but also with her knowledge and experiences.”

Birmingham grew up in Fitchburg, Massachusetts, where her father, a postal worker, and her mother, a teacher and homemaker, nurtured her love of learning. “I was always interested in how things worked together, and I liked math,” she said. “And then I discovered physics!”

A scholarship to the School of Engineering brought all those subjects together, where, she recalled, “Dean Burden was always supportive of women students.”

In 1997, she and her husband, who built a successful career in finance, established a foundation that runs a program called Step Up to Excellence, which expands educational and cultural opportunities for high school students from low-income homes in Fitchburg, Framingham, Clinton, and Stoughton. “Through my work with Step Up, I learned quickly that it’s not just lack of money that holds young people back,” said Birmingham. “I realized what a culture shock it is to go off to college. That’s why the Center for STEM Diversity seems like such a good fit for me.”

Alejandro Colina-Valeri, E21, is one of many students whose lives have been transformed by her gifts. Through the Tufts in Talloires program, he traveled to Lyon, Paris, and Switzerland, “and I also took two classes that I normally wouldn’t study as an electrical engineer: Flowers of the Alps and Animation. It was the best summer of my life.”

That feedback affirms for Birmingham that each and every gift goes a long way. “I’m overwhelmed when I hear student stories,” she said. “There are so many young people out there who just need somebody to open a door for them, and to say, ‘I care about what you’re doing.’ You don’t have to do a huge thing to make a big difference, but it is important to do something. It’s important that all students have a chance to talk with and listen to many different people—how else are we going to make progress?”